UPDATE: Okay Denverites, I just got word from Keith Garcia at the Starz Film Center that The Secret of Kells will make a triumphant return to Denver starting April 16th. Mark your calendars!

The Secret of Kells is not an American movie, but it is a movie that could teach Americans a lot. The Irish animated feature that received a surprise “Best Animated Feature” nomination alongside genre-giants from Pixar, Disney, and Wes Anderson of all people wasn’t on many peoples’ radar, which is unfortunate because this movie deserves a much wider release. The Secret of Kells, set in the Abbey of Kells in the ninth century, finds the peaceful and typically scholastic monks and villagers faced with the mortal threat of “Northmen” invaders. Abbot Cellach leads the construction of an enormous wall around the Abbey, and doesn’t mince words in his harsh criticism of the monk ‘illuminators’ (think ‘bible artists’) who seek to continue their work illuminating the Book of Kells rather than assisting in the fortification. Caught in the middle is Brendan, Cellach's nephew and an orphan. We immediately note Brendan’s acute perception and appreciation of the beauty and wonder in the world. Though the illuminators have taken Brandon under their wing, his uncle does not approve.

This is maybe five minutes into the movie, but already you can see motivation and conflict far more mature and difficult than your average Disney – hell, even Pixar – movie. There is no ‘bad guy’ – the ‘Northmen’ are not portrayed as a human threat, but more like a force of nature. No, the central conflict in The Secret of Kells stems from whether it is more important to protect the people of Kells themselves or the ideas of Kells. On the one hand, Abbot Cellach seeks to protect his people from the very real threat of physical annihilation, and is absolutely willing to forgo the preservation of their culture. On the other hand, the illuminators question the point of saving Kells’ people if their culture is lost or mutilated. I appreciate that this is not a one-for-one exact metaphor for contemporary affairs, but the questions asked here about Medieval Kells are the exact questions we should ask of our own cultural heritage, and exactly the questions that don’t typically get asked. What is our importance? Is it the preservation of our physical bodies or of our ideas? And is the preservation of our bodies worth losing our grace?

The Secret of Kells presents a glossed-over version of Christianity that I haven’t quite wrapped my head around yet. The Book of Kells is made up of the four Gospels, but we’re talking pre-Martin Luther-secular-language-translation Latin Bible. Not many if any at Kells can read it, and the illuminations the monks work on aren’t direct illustrations of iconic Bible stories or verses. Indeed, God or Jesus hardly come up, if ever; the concerns of the inhabitants of Kells are much more immediate than that. What’s more, in his travels in the forest surrounding Kells Brendan encounters a youthful wood-nymph and serpentine Celtic underground monster, and his nonchalant acceptance of these Pagan creatures reveals a Christianity very different from the one we know today. Christianity in The Secret of Kells is one supernatural subscription amongst many, and while it doesn’t preclude the existence and viability of other creeds, it furnishes our protagonists with real grace and honest to god Christian charity…what a novel concept!

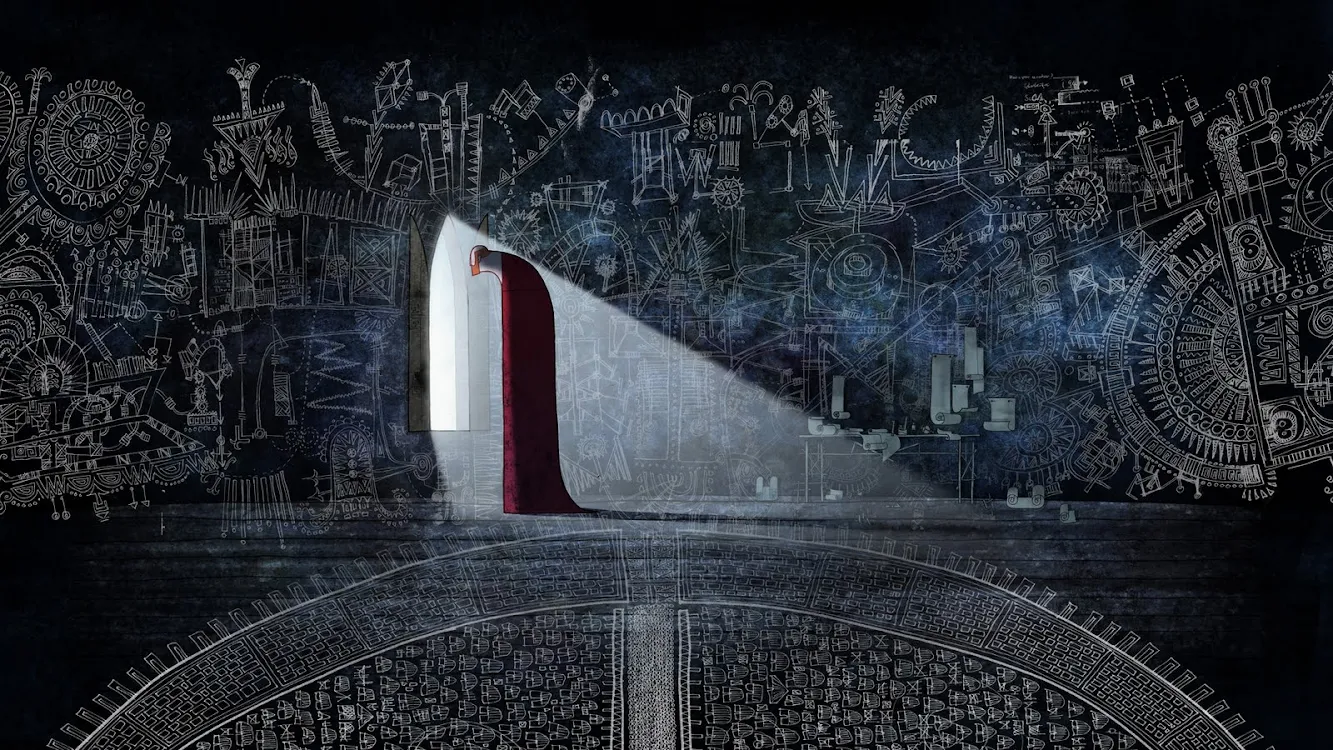

Take or leave all that, but you will not be able to deny that the animators have created an animated world unlike anything ever put to film. The Book of Kells is the movie's aesthetic Rosetta Stone. Yes, the Book is real, very famous, and very cool. The Book of Kells dates at least the ninth century, waaaaaay predating any Renaissance or Neo-classical interest in the ‘realistic’ depiction of three dimensional space. So follows the animation in the movie, the simplified bodies and clothing of the monks, the spaces of the abbey rendering depth on a flat plane from bottom to top rather than with perspective, and the stylized reduction of objects to pattern. This is not idle decoration, however, rather speaking to the perception and worldview of the characters themselves. This is not the era of science and rationality, it is the time of medieval mysticism and a world perceived through natural and supernatural order, chaos, and spirit. Furthermore, the animators don't limit themselves to strict rules concerning space and technique. There are examples of three dimensional space and other more contemporary perspective throughout The Secret of Kells. This was the right decision, and lends flexibility and life to a style typically rigid and alienating to modern viewers.

If The Secret of Kells is playing near you it is an absolute must-see. Don’t think twice about it. Whether you come out loving it as much as I did or not, you will have plenty of food for thought. In animation, 2009 was a year for the record books. That The Secret of Kells might not even be my favorite or even second favorite animated movie last year should speak very highly of the caliber of work that was released. Up, Ponyo, The Fantastic Mr. Fox, and The Secret of Kells are all classics, and some of the most outstanding and noteworthy works in feature-length animation in the history of the medium. We are living in an animation Renaissance. I hope everyone realizes that.

Magic Moment: Brendan and the wood-nymph Aisling climb an impossibly tall tree, and the trip from bottom to top takes them through a kaleidoscope of design and perspective. Each different shot is a distinct vision and world apart from the others. Finally they emerge above the leaf cover and the music swells to deafening volumes as they bask in the sunlight under a canopy of butterflies.